Dear Friends,

It's been a long time. I am writing to you from the island of Crete, hiding out here after spending a summer at Bard College at their low-residency MFA in moving image. I haven't written to you since my Pandemic diaries in 2021, amidst the chaos of the Shanghai lockdown—and I am no longer embarrassed to admit I haven't written much in life either. I felt such resistance to writing after seeing how language failed over and over during the lockdown, and how I chose to erase myself during that time. Perhaps to get to that I will begin here, in Crete, how I am slowly finding my way back to writing.

I have been thinking about the ways we use language to construct meaning from our lives. I am thinking about this because I am noticing the sharpness of the world after a recent break up, how life always seems to emerge with its edges, sharp and lucid, after a painful encounter. I am wondering about this as I am unable to tell the story of our relationship, it is as if I am without words. When friends ask me what happened, I do not know where to begin/ end, words seem futile, because I cannot craft a narrative around what happened, to inject it with meaning, because there is no sense in its linearity, and I cannot contain its overflow.

I can point to one thing that led to the next (and the next), but all that feels superficial, there is no cause and effect, circumstances cannot be strung together like beads on a chain. I find myself resistant to making sense; there is no coherence to be shaped.

I was especially irritated when in recent days, I was spending time with a friend. We were catching up after many years apart, and as I listened to her speak, I suddenly felt that she was endowing every little thing in her life with meaning—she gave name to every detail of her experience, she stressed again and again who, where, how, she became the way she is, her origins, her father, her mother, her friends, her experiences, her lovers, and I suddenly felt so nauseous from what felt like over-saturated meaning-making I needed to turn away.

Everything felt so clearly defined, and given language to, and yet it was too contained, meaning didn't make sense within the orderliness. Narrative felt worthless; and I felt lost amidst an unnamable chaos. Which is in stark contrast to how I usually feel— I love and honor poetry because writing poetry feels like persistent offerings, daily glimpses into what is worthy of meaning-making in life; what makes life worth living.

I have always felt poetry is a form of prayer for the living, that it is precisely due to its ability to magnify the insignificant, to call into being the inconsequential ordinary, that I love it, as a study in paying attention. And in the best moments, under the particular way of light in Greece, I am able to find significance in the way the seaweed is entangled around my foot, the luminous quality of this water on the colored pebbles, the constellation of mosquito bites.

So what was so off-putting about this over-saturated construction of narrative? And isn't that what I am attempting to do always, in my work? When my friend pushed me to speak-- she could sense my irritation-- I felt myself anchored in silence. An exhaustion of the body, heaviness of limbs, my throat closed up. I ended up brushing her off to say that I can't speak because when I am writing I sink into this deep, bodily silence.

And that part is true. I wanted to come back to Greece because it was the last time I found a good writing rhythm, when I was here for the NYU residency in Jan 2020, right when Covid hit. When I was monitoring the news in China from afar, and then masks started disappearing from stores here. I was able to write every morning because I spent all my time alone in Athens, and had fallen into a silence that allowed me to hear the clattering inside me, with more clarity, and I did a lot of thinking along the "poetics of witness," you may remember I wrote about it here.

I have been thinking about writing this letter now for years, to explain my abrupt absence after the pandemic diaries, last written in 2021 (I can't believe it has been so long). I am grateful for everyone who wrote me during that time, and apologetic about not having the capacity to respond. When I think back to those years, I draw a blank-- as many of us do, that strange time-warp of the pandemic.

Here is what happened. When I published those diaries, and started re-blogging them on my Twitter, the posts took off. I got tens of thousands of likes within a few hours. The comment section became a war on "dystopic" covid policy, and then trolling about China. My inbox was flooded with comments and requests from major publications and news agencies around the world-- I found myself quoted as the "FangFang of Shanghai" (writer FangFang, who was indeed my inspiration for the Pandmic diaries, was later exiled). I was unable to check my phone without fear.

I wanted to be seen, and yes, heard, but not in this way. I felt like I was becoming the face or mascot of how the West wanted to portray a "dystopic" China without my consent, which is of course how the internet/ news works. Many friends and mentors called to urge me to delete the posts before I got in more trouble. They said I would never be able to find a job after this, amongst other larger threats. And after many sleepless nights, I did.

The thing is, at the time, amidst the height of the lockdown, those diaries were my only way of anchoring myself to meaning. I felt such urgency, that I spent all day collecting and archiving information about the lockdown, and trying to write about it with some form of coherence into the early morning.

It all began here: the head of psychiatric hospital saying, regarding imminent lockdown, “We have to control the soul’s desire for freedom.”

I rarely slept, because well, we were in the house all the time so there wasn't a real break to the days-- but more importantly, because the Shanghai internet was on fire. It was the most radical internet within the firewall I have ever witnessed, precisely because it was the most vigilantly censored. Everything was erased within hours, minutes, and thus, people posted more recklessly than ever before, in a race against erasure.

Most posts you click in would say [404], gone. So people re-posted everything with urgency, and with immense creativity, photoshopped every which way, upside down, mirrored, condensed inside cartoons, in a race to beat the censors. It was the most moving and creative way of using language and image -- for survival! to be heard! to be seen!-- I have ever seen.

And we stayed up all hours of the night because the censors were more likely to be asleep at night. So the internet blossomed into an arena of freedom-- but of course, also of desperation and appeals for help. Injustice documented, reblogged, and inevitably by morning, erased. The cycle repeated hourly.

I raced against erasure to save everything, write it down, somehow give it a sense of coherence for those not in Shanghai, who do not speak the language. (Rumor also has it that the Shanghai internet was siloed in a way that only those living in the zones could see it, but hard to prove.) Writing and documenting gave me a sense of purpose amidst the terribleness of the world, the lack of sense of why it was all happening.

My memory falters now because inevitably, I had erased those diaries, and by erasing my digital presence, my narrative, the ways in which I make sense of the world, I erased myself.

After I erased them, I woke up to posts circulating about "Shanghai poet disappeared," absurdly along with an image of a blue twitter bird wearing a medieval plague mask, with an arrow in its heart, assassinated. I felt disgust, but mostly in myself, I had chosen to disappear myself. I erased everything I stood for, especially in this role of "witness" I had been thinking so long about. I had no one to blame for the arrow but my own hands.

I wrote nothing after that. A year later, on the anniversary of the lockdown, I made a secret performance/installation called "108 Days" in an underground club in Shanghai. In which I put my diaries in bags of discontent noise, you could hear my voice if you pressed your ear to them with care. I turned to other modes of making, without the clarity of writing which I had always hidden within, because I could not find sense to be made, because I was resistant to the boundaries of meaning drawn up by language.

Sound installation “108 Days”: Shanghai was locked down for 108 days, which is also the number of days for reincarnation in Hinduism

This led me to an interest in the materiality of things, and making films, which felt tangible, and real, but also obfuscating of me, what I did not know how to say. And finally it led me to my time at Bard this summer.

And now here I am, wanting to write about the ways we weave and unweave narratives about ourselves, how in the blue of a break up, everything is blessed with meaning. The moment of taking a breath emerging from the dull surface. The sudden coldness, the sudden sense of self. Somehow a newness, complete without reckoning.

what would you hear if you could?

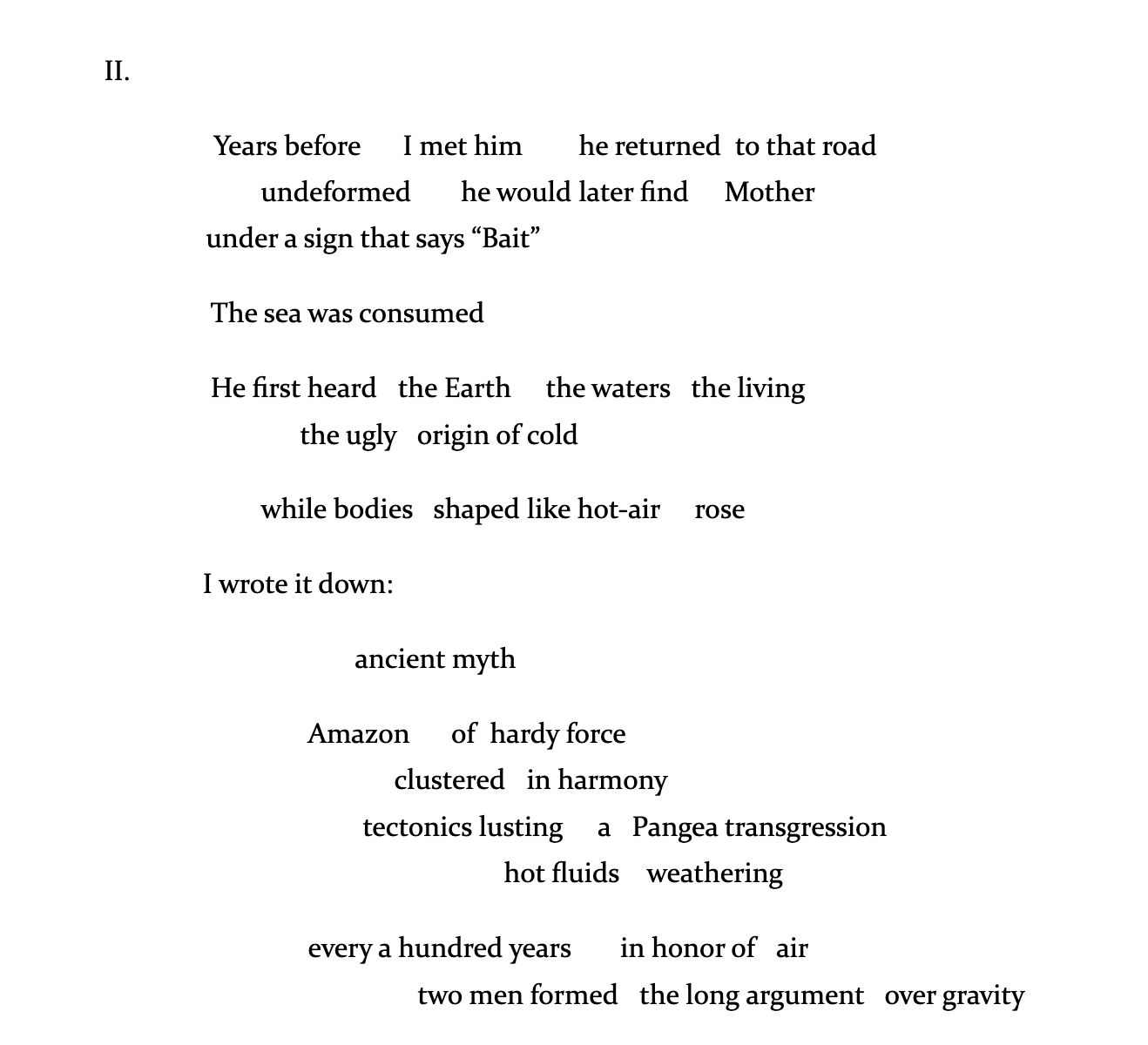

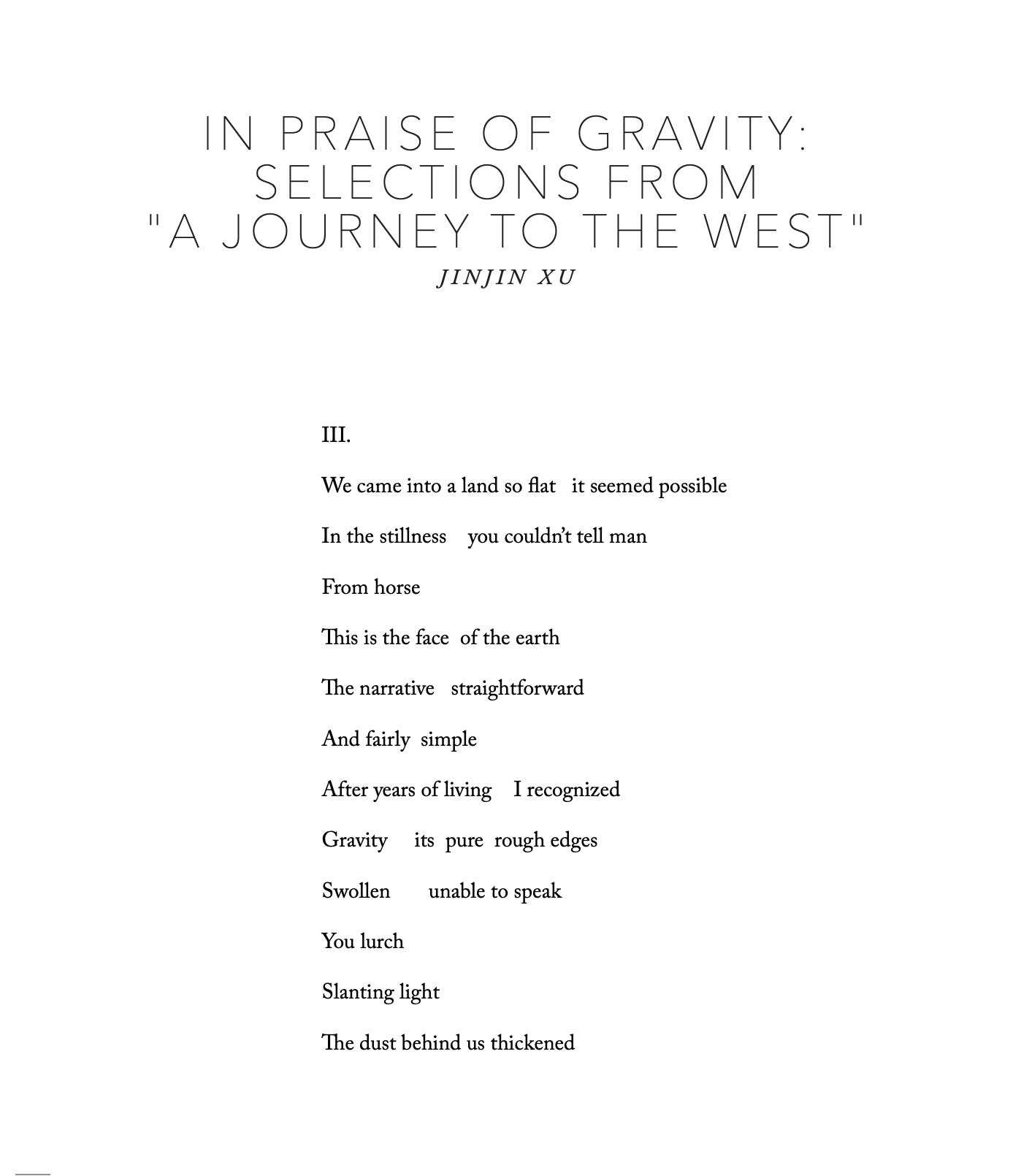

On the note of erasure, I wanted to share with you these excerpts from my series of erasures "A JOURNEY TO THE WEST.”

I stumbled upon excerpts of John McPhee’s “Assembling California” in the 1992 New Yorker during the years I did not write. McPhee’s text—a narrative informed by his geological field surveys across America with tectonicist Eldridge Moores—calmed me. Human and geologic time merged, unraveling the epic undercurrent to our ordinary realities: California was once “only blue sea reaching down some miles to ocean-crustal rock.”

Yet, beneath the shifting tectonic plates, murmured a collective voice, something ancient, buried. They guided my ears through the text. When I erased the text, there we were. We have always been there.

To excavate the Chinese from the text is to unbury us from the land. McPhee rarely mentions “China” or “Chinese”—despite the Gold Rush, despite our ancestors beneath each track of railroad built. What McPhee did mention: “from Gibraltar through China”; “A Chinese miner wounds a white youth and is jailed.”

The Anthropocene is directly responsible for the climate crisis. Despite the billion-year ruptures and formations, our brief existence has caused a human disruption of geologic time—caused by our exploitation of resources, our treatment of land, rooted in the American empire’s continuous erasure of history.

To be aware of our ecological impact means a shared consciousness of our buried, collective history: of the land, of us. Only then, will the geologic and Anthropocene merge.

Voices arose from the text; we have always been here.

They spoke; I wrote it down.

These two excerpts below were published by LARB and The Margins in 2021 and 2023.

FROM A JOURNEY TO THE WEST

II. THE LONG ARGUMENT OVER GRAVITY

yours,

JinJin